Retired Army Col. Franklin Childress has spent the past two decades ensuring the legacies of soldiers never die.

Childress was assigned to work at the Pentagon just days before the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. If delivery of his household goods had not been delayed, there is a good chance he would have been at his office that Tuesday morning.

Instead, he was sitting outside of temporary housing when he heard a “sonic boom.” He says he had no idea what had happened.

“I didn’t have a clue that the Pentagon had been hit; I didn’t have a clue that the World Trade Center had been hit. I was just sitting there, no TV, just journaling. At about 10:15 or so, my pastor from Hawaii called me and said, ‘Franklin, are you alright?’” Childress said. “I felt like the world was ending… I put my uniform on and went down to the Pentagon.”

But the FBI wouldn’t let him in because it was deemed a crime scene. Childress said he felt useless as he watched smoke billowing from the building. Soon he would learn that many of the people who were his new colleagues — including his sponsor — had died that day.

“Immediately I kind of felt survivor’s guilt because I was supposed to be there, and it was a miracle that I wasn’t… I felt like, ‘Why am I here and so many people were killed?’”

But he later realized what his new purpose would be.

The South Carolina native grew up in the small town of Laurens, where he was raised by a father who “never wanted to leave the county.” The concept of military service was introduced to Childress during his teen years when someone brought up the idea of ROTC.

“I kind of found my calling in the Army,” he said. “I went to Air Assault School while I was in college. I was the operations officer at the ROTC detachment. I basically just went whole hog Army… Everything I did in college, just about, was Army.”

He described himself as “one of those guys that is living the American dream,” with his career taking him all over the world. Childress says that because of his assignments and experiences, he was no stranger to death — but death happening at home was something new to process.

“An attack on the homeland. It was the seminal moment for a generation,” Childress said. “I was a lieutenant colonel; I had served as an airborne infantry ranger, doing all these things and then … as a soldier to have it happen in the homeland, it was really an enemy attacking us here. I felt very angry and on edge because what’s going to be the next thing that happens here?”

From Sept. 14, 2001, through Jan. 26, 2002, Childress attended funerals for those who died. The backdrop of the services at Arlington was the gash in the Pentagon. He recalled the eeriness of it and how depressed he felt.

His role at the Pentagon morphed because they needed somebody to handle media inquiries for what was going on with the heroes, victims, and survivors.

“I felt I helped by helping the victims’ survivors,” Childress said. “Telling their stories was very cathartic to me, and it gave me a sense of purpose and a sense of meaning for my life.”

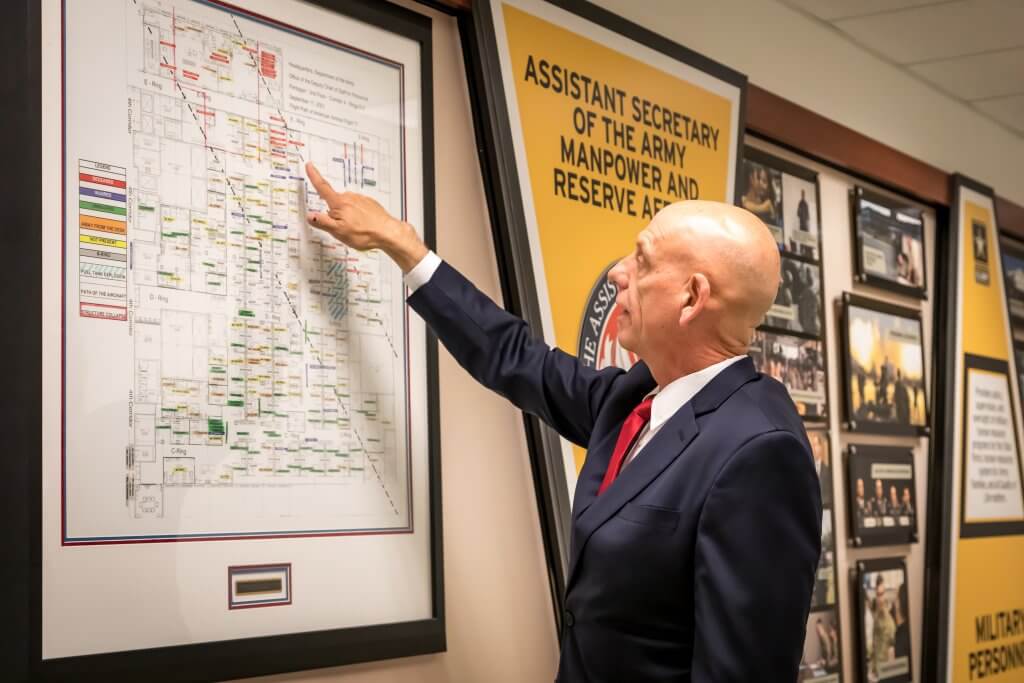

In the months and years that followed, Childress has remained committed to the singular phrase, “Never forget.” He advocated for soldier’s medals, organized a memorial service, and helped create a memorial within the Pentagon that showcases the names and images of those who died — a project he called a “labor of love.”

Childress went on to retire from the Army after 30 years, but today finds himself back at the Pentagon as the deputy director of Army Reserve Strategic Communications. He says that no matter how much time passes, that day never leaves him.

“It always stays with me, to be honest with you,” Childress said. “When I walk down that corridor, to see those faces brings back those memories. They’re never far from me. … I never forget those people. We don’t need to think about Sept. 11 as a thing that happened far back in history. We need to remember it and remember that it can happen again. We can never allow something that horrific to happen again.”

Read comments