Within his first week in Iraq, 8-year-old Rexo tore a ligament in his shoulder. He neither whimpered nor whined – and actually outperformed some of his younger, fellow four-legged soldiers.

“He was definitely the best dog … He was outstanding,” said Staff Sgt. Nelson Struck, of the Connecticut National Guard’s 928th Military Working Dog Detachment.

Rexo and Struck were paired for two-and-a-half years, but the hardest bond to break was with his first dog, Zora.

“I completely sunk my heart into her, and I got really really attached, and when I had to get unpartnered for her, it really screwed me up for a while and I had a lot of feelings,” he said. “Then I got assigned to a different dog and then I got assigned to a different dog and every time I got reassigned it was easier.

“I build good bonds with my dogs still, but I’m not as attached as I was. Like, I’m reassigned to my fifth dog now, and I’m building a really good rapport with him … but if I have to pass him off, I’m not going to think about it for a second.”

Struck said he has a “vested interest” in the health and welfare of the dogs but letting go has gotten easier over the years. And that’s exactly what’s entailed for the only K-9 unit in the National Guard.

Connecticut K-9s

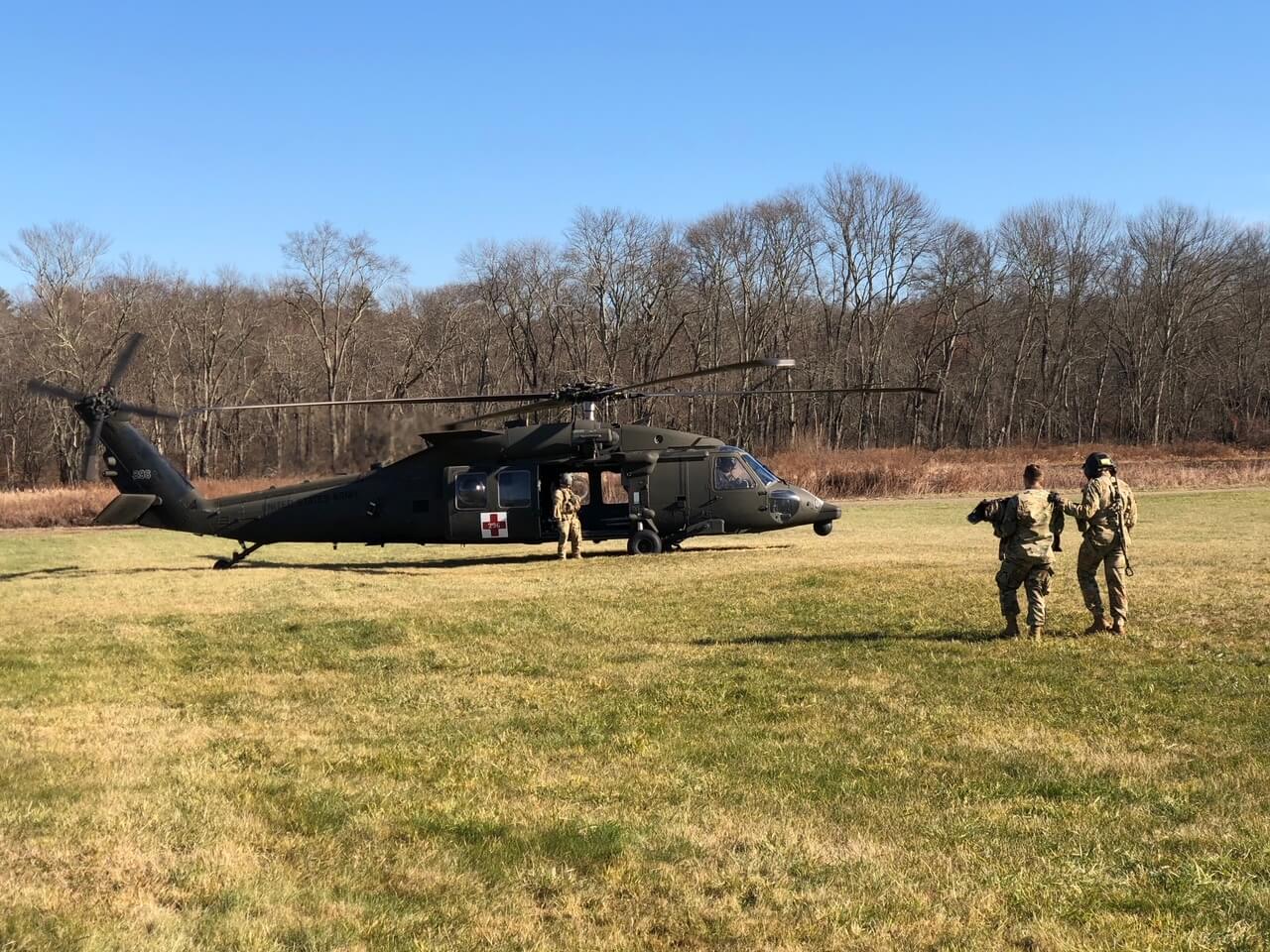

The 928th Military Working Dog Detachment has nine dogs – German Shepherds, Belgian Malinoise and a Dutch Shepherd – and nine handlers, in addition to Kennel Master Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Rufini, and his plans NCO.

“[The National Guard] tried to emulate other kennels that were out there and the building that they used was actually an old pig barn back in the day,” said Rufini, who has been with the unit since 2013.

RELATED: Organization Puts Service Dogs on Front Lines of PTSD Treatment

Construction for the Connecticut detachment’s kennel began in 2005, but until they had their own working dogs Rufini said guardsmen drove to a Navy base across the state to observe and learn from dogs located there. Once the 928th had its own canines, it was a matter of training and third-party certification.

“We have to travel to an active-duty base to get certified by the Department of Army Certification Authority. Basically, someone who’s an outsider with the military working dog program on the active-duty side,” Rufini said.

Certification includes a basic obedience course where the dog navigates obstacles, a blank gun is fired to show the dog won’t run away or attack the handler, bite work and detection. The process takes about one week.

Training at Lackland

Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland oversees the working dog program, regardless of where the K-9s ultimately serve. Service members like Struck, who has been with the 928th since 2014, participate in the military working dog basic handlers course.

Master at Arms Petty Officer 2nd Class Brianna Flores, a petty officer, has been a member of the 341st Training Squadron at Lackland since July. She said trainers who come through Lackland typically have a basic understanding of working dogs, but – “getting here, you don’t know anything.”

“It really humbles you very fast because out in the fleet, or out in our respective services, we know how to work a dog that’s already came to us,” Flores said. “Here we’re training while our dogs are training.”

Rufini said the dogs go through roughly 60 days in detection training, either for explosives or drugs; patrol for 60 days and learn basic obedience, how to find people in the woods and controlled aggression. The canines also learn to not react to gunfire and to search buildings.

Flores said participants can train and qualify a dog, but it doesn’t necessarily mean the dog will go back to their branch.

As a joint-service school, Struck said, Lackland provides an environment to train alongside airmen, Marines and seamen.

“It’s really interesting because you get exposed to all these different ways that the DOD as a whole kind of conducts themselves, which as K-9 [handler] really helps you out going forward because we work with literally everybody.”

Training for patrol

All of the dogs in Connecticut, according to Rufini, are trained for dual purpose – patrol and detection. Trainers typically begin their work with the unit on the narcotics side.

“It takes a while to have things become second nature, so we always approach it like we’d rather you make mistakes on the drug side,” Rufini said.

Because the unit is Active Guard Reserve, they work every day of the week, Rufini said, and are constantly training.

“We travel to different locations to take advantage of different training opportunities they have, whether we can go to a large motor pool at an armory … [or] go to a movie theater and search in that environment.”

As a Guard unit, the detachment conducts base support and provides “random anti-terrorism measures and force protection to the state of Connecticut.”

They also coordinate with the Department of Homeland Security, TSA, Customs and Border Protection and local law enforcement, according to Rufini, conducting random sweeps and supporting West Point Military Academy on an interim basis.

The unit also has an ongoing deployment rotation. Currently, they are in CENTCOM supporting Operation Inherent Resolve, but have previously deployed to Qatar. The kennel also supports the Secret Service upon request.

While Struck is transitioning to a leadership role – and planning to adopt his first dog Zora – he said helping the “next generation of handlers” has been the most rewarding.

“It’s pretty awesome,” Struck said. “We work with everybody under the sun. Our training is crazy and our deployments rock. It’s the best. It’s a career field that matters.”

And Struck’s battle buddy Rexo? He is retired, adopted by Rufini – also one of his previous handlers – and was being “dog-sat” by Struck at the time he spoke to Reserve & National Guard Magazine.