When Tennessee National Guardsman Andrew Lee began facing his post-combat demons, he found his salvation in an unlikely place: at the controls of a specialized longarm quilting machine.

And he doesn’t care what anyone thinks about it.

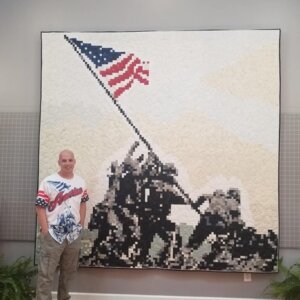

“When I’m teaching at RTI [the National Guard’s Regional Training Institute], I say, ‘Hi, I build cars and I’m a quilter sponsored by six companies,’” said Lee, a staff sergeant. “People are like, ‘Oh, haha,” but then I show them pictures of my Iwo Jima quilt, and one time an E-7 said, ‘That’s not your grandma’s quilt.’”

Lee, a National Guard instructor, never imagined when he joined the Army as an active-duty soldier in 1997 that he would one day be known as the “Combat Quilter” with works in museums. Before enlisting, he had taken design classes and aimed to be a graphic designer. His mother used to corral him into helping “make those stupid country bunnies” popular in the 1980s, he said, but his sewing experience ended there.

Lee, a National Guard instructor, never imagined when he joined the Army as an active-duty soldier in 1997 that he would one day be known as the “Combat Quilter” with works in museums. Before enlisting, he had taken design classes and aimed to be a graphic designer. His mother used to corral him into helping “make those stupid country bunnies” popular in the 1980s, he said, but his sewing experience ended there.

But then came deployments to Iraq in 2006 and 2009, with all the emotional and mental trauma that often accompanies them. Lee came home feeling emotionally numb, sometimes watching “Undercover Boss” just to feel something at each show’s usually heartwarming end. Prescription drugs nor alcohol weren’t helping allay his anger and frustration, either.

“We don’t do enough together,” his wife, Kristy, said one day in 2016, several years after he joined the Guard. Soon after, a flyer advertising a class on quilting table runners arrived in the mail. They gave it a shot — and Lee soon found himself hooked.

“I could put my sewing machine up in the middle of a concert now and not know what anyone else around me was doing,” Lee said. “On those days that I don’t sew, I can feel my angst and anxiety getting worse.”

Early on, Lee got involved in a male quilter group connected to Quilts of Valor. The charity provides high-quality quilts to nominated veterans and service members. Lee awarded the first quilt he ever completed to a 93-year-old World War II veteran — and he unexpectedly felt real, long-dormant emotion.

“The moment of Mr. Carpenter’s gratitude is what got me to feel differently than I’ve ever felt,” said Lee, who estimates he now spends 60-65 weekly hours in the quilting world. “This is something you can put your hands for the rest of your life.”

Today, Lee has made nearly 700 quilts (though his personal collection only consists of five) and regularly teaches quilting classes at guilds, retreats and even on cruises.

A Tennessee quilting guild is how Arliss Barber, leader of a Quilts of Valor program in Loudon, met Lee in 2018. She immediately noticed his intelligent nature and endless energy.

“He’s a fast learner,” said Barber, the daughter and wife of veterans. “It’s made him a bit of a superstar, which is what we call him.”

At least once, one of Lee’s quilts — usually 60 by 80 inches, or “nose to toes,” as he calls it — has prevented a combat veteran from following through with suicide. To keep that veteran-to-veteran support going, Lee is buzzing with future plans, including building a quilting retreat center with free classes for military members.

Barber isn’t surprised. “It usually takes a number of years to get where Andrew’s at, but he’s gotten there in a relatively short amount of time,” she said. “That man can probably do more in 24 hours than we could in five days.”

Call it an obsession or mission. It’s all the same to Lee.

“I’ve got to make quilts,” he said. “It’s my only way to survive.”