Editor’s note: This is part one of a three-part series across AmeriForce Media publications.

When the suicide bomber hit Abbey Gate at Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) last August, Army Lt. Col. Jake Helgestad rushed to the scene.

Along with a surgeon, a physician assistant and two medics, the Minnesota National Guardsman and his team helped the 1st Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division, in the mass casualty event that followed.

“That was very unique, just a moment in time where I had that capacity and had the expertise to be able to help with that whole situation,” said Helgestad, a former 1st Combined Arms Battalion, 194th Armor Regiment commander who led a portion of his task for into Afghanistan to assist with the evacuation of Afghan citizens.

Later, his task force was asked if any had served as a Marine. Helgestad had.

“I was able to go to a dignified transfer when they put the 13 caskets into the plane … It’s one of those things I will never forget,” he said, referencing the 13 service members who died in the bombing.

‘Organized chaos’

Helgestad’s unit originally deployed to the Middle East, though he said planning began in July in the event they would be tasked with going to Afghanistan.

At 11:22 p.m. on Aug. 12, he was woken up to the news that he needed to be in Afghanistan in 24 hours. The following morning the task force was notified.

“It kind of became organized chaos, where everybody went in different directions … and then we just started working everything,” Helgestad said.

Of the roughly 1,000 guardsmen under his command, Helgestad took 425 forward to Afghanistan, 75 were on a mission in Syria, another 100 were on a separate mission in Kuwait and 400 remained at Camp Behring, Kuwait.

His task force members in Kuwait assisted with processing the evacuees’ move to the U.S. and conducted 5,500 medical screenings.

“We honestly had no idea what we were going to do,” Helgestad said of those heading to Afghanistan, “and by that what I mean is, I moved to the airport on Saturday the 14th in Kuwait and stayed down there with the first 200 people … And we literally just stayed there because we didn’t know when our plane would show up.”

On Aug. 14, the U.S. embassy closed. At one point, Helgestad’s mission was to go to the embassy – then it changed again.

“Then it changed to when you get here, we’ll figure it out,” he said.

‘No idea what it would be like’

The task force members, according to Helgestad, had good morale heading into the mission, though there was some uncertainty because 80% of his men and women hadn’t deployed before.

“There was that nervousness,” he said. “So when our first flight went out, first two flights, myself and my chaplain said a few things … At that point, we literally had no idea what it would be like when we got on the ground.”

RELATED: Reserve airmen ‘bewildered’ as Afghanistan evacuation unfolded

While refueling in Qatar on the way to Kabul, Helgestad said he witnessed six NATO jets take off for patrol in Afghanistan. That’s when it hit him.

“The enormity of the whole thing, that was the first moment,” he said.

This was the Minnesota guardsman’s first time in Kabul, and initially, it reminded him of the mountains of Colorado Springs, Colorado.

“This place is really beautiful, then the machine gun fire [starts], and you get brought back to, ‘Holy crap, we’re in Kabul,’” he said.

Initial chaos transitioned to problem solving and his guardsmen using their civilian skills at the HKIA itself.

“I had joked, ‘Yeah, I have a guy for that,’” Helgestad said. “We have people that have life skills.”

Guard involvement in Afghanistan

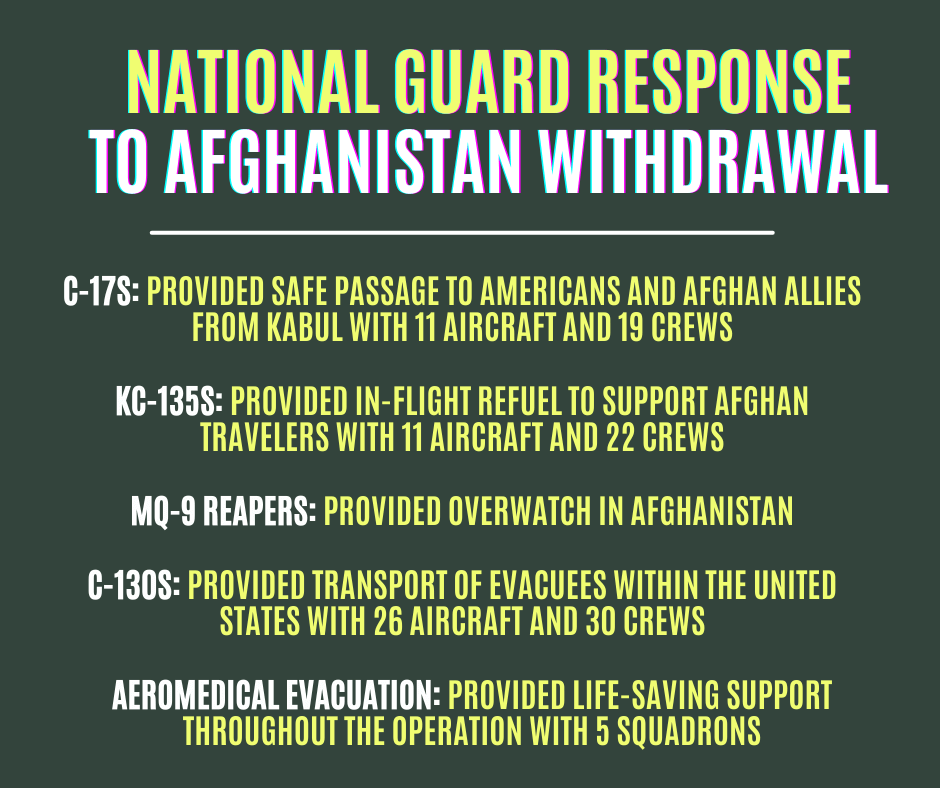

At the peak of Operation Allies Welcome, more than 1,300 guardsmen were on Title 10 orders supporting the mission, and the Guard “expended more than 82,000 mandays,” according to data provided by the National Guard Bureau.

As of Feb. 4, 2022, guardsmen had been involved with more than 48,000 evacuee relocations through OAW, Guard data shows.

Doug Livermore, advocacy committee chair for the nonprofit No One Left Behind and a guardsman himself, deployed to Afghanistan from June 2013 to February 2014 with the 3rd Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group out of Fort Carson, Colorado. While he didn’t have contact with Afghan allies and interpreters daily, he said he did “plenty of battlefield circulation” and saw the extent to which service members relied on their Afghan counterparts.

When evacuations began last year, there was “immediate recognition” that the situation “was going to devolve very quickly,” according to Livermore, though he doesn’t think anyone expected Kabul to fall so soon.

But before its fall, NOLB had already been coordinating commercial air flights for those granted special immigrant visas (SIV) and their families. So they “already had mechanisms in place to receive and spend money for evacuations, according to Livermore.

Understanding the ‘immensity’ of the Afghanistan situation

The mission for Helgestad lasted only two weeks – Aug. 17-31. Uncertainty gave way to the rhythm of 12-hour work shifts, and the task force “owned a section of the airport,” through which roughly 30,000 Afghans evacuated.

The Guard team took control of security, then put into place a plan to withdraw. All from scratch.

“It was literally just an idea … to two weeks later put into action and actually seeing it develop and us leaving,” Helgestad said.

No One Left Behind reported in early August that it has helped evacuate nearly 1,800 people since August 2021 and is tracking more than 69,000 SIV principal applicants and their families still in Afghanistan.

Army Reserve Col. Greg Fairbank, who serves as chair of NOLB’s finance committee, was in intelligence on a past Afghanistan deployment and said that work is an important part of why he joined the board.

“We asked a lot of these people to work with us and work with us in many ways,” he said. “And if we don’t fulfill our commitment to these people, they won’t do it in the future. It’s the moral thing to do in terms of fulfilling our promise.”

And that’s why, to Fairbank, the events of last August were “so disappointing.”

“We withdrew. We left so many of these people there … It’s awful. We left these people behind, and from my perspective – it’s not the moral thing to do, and it’s going to make things much harder in the future for us,” he said.

So far in 2022, NOLB has helped nearly 650 SIV families resettle in the states.

But for the men and women who served with Helgestad, he had a question for them – 20 years from now.

“Do they understand the immensity and the enormity of what we did, and will they 20 years from now?” he said.