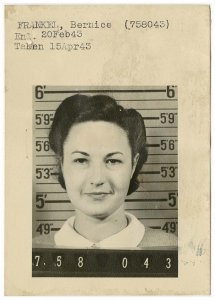

Fellow Marines surely were thankful that Bernice Frankel was a friend, traveling down the road and back again – as a truck driver in the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve during World War II.

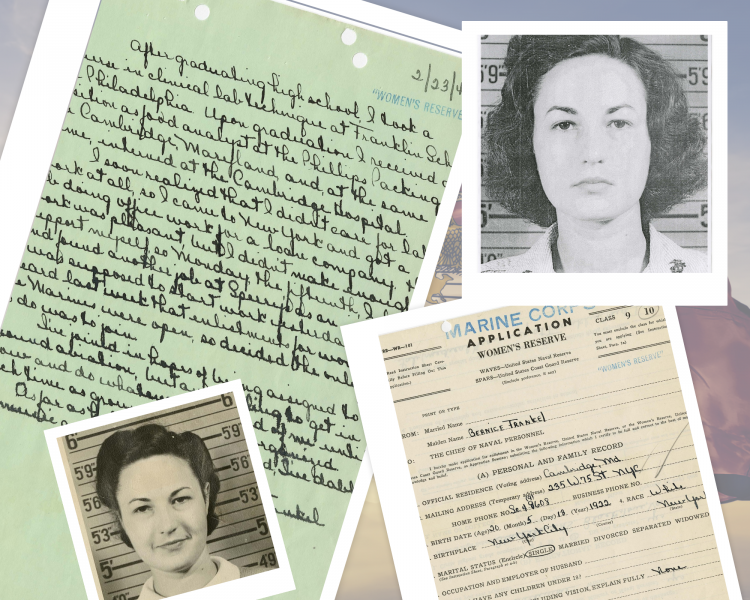

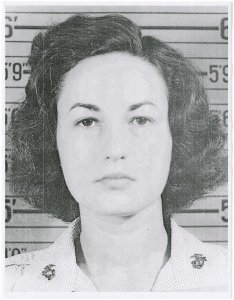

Frankel – better known as Bea Arthur – portrayed the brazen Dorothy Zbornak on “The Golden Girls” and staunch feminist “Maude” as that show’s namesake. She flat-out denied her military service while alive, but service records maintained at the National Archives confirm she was, in fact, a friend and a confidant for the U.S. Marine Corps.

“Her service becomes like evidence of badassery,” said Dr. Kate Browne, author of the 2020 Wayne State University Press book, “The Golden Girls.”

Despite the public denial, Browne said there’s no question that Arthur’s stint in the Marines made sense.

“I think there’s a loyalty,” Browne said. “[She’s] got that sort of quality, being an introvert with people and, later in life, being so politically active with different causes, it makes sense to me if there were a call for service in WWII, she would answer that call.”

Bea-coming a Marine Reservist

And answer it she did, applying to join the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve at 20 years old, mere days after its creation.

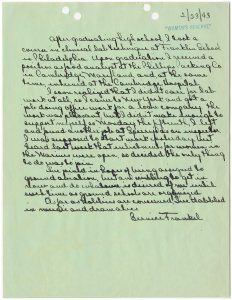

A letter Arthur penned in February 1943 stated that she worked at Phillips Packaging Co. while interning at Cambridge Hospital after graduating from high school.

“I soon realized that I didn’t care for lab work at all, so I came to New York and got a job doing office work for a loan company,” she wrote. “The work was pleasant, but I didn’t make enough to support myself. So Monday, the fifteenth, I left and found another job at Sperry’s [sic] as an inspector. I was supposed to start work yesterday, but I heard last week that enlistment for women in the Marines was open, so [I] decided the only thing to do was join.”

The women’s reserve was established in February 1943, providing the opportunity for roughly 20,000 women to serve in 200 different capacities.

In 1941, Rep. Edith Nourse Rogers, a Red Cross volunteer during World War I, introduced the bill that established the Women’s Army Corps. The following year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Public Law 689, which created the Navy Women’s Reserve. The Marine Corps also fell under the Department of the Navy, according to Kali Martin, National WWII Museum research historian.

“It’s important to note there, [the public law] didn’t require it, it just allowed it,” Martin said of women serving in the Navy.

Amid the hesitation that Martin said existed in the ’40s regarding allowing women in the military, the Marine Corps was the “most reluctant.” It wasn’t until Nov. 7, 1942, that Commandant Lt. Gen. Thomas Holcomb approved the formation of the women’s reserve.

“Everything kind of moves quickly from there,” Martin said. “[They] have to start figuring out how many women do they need, what are they going to be capable of.”

Despite the Marines’ hesitancy in letting women in the branch, according to Martin, it was the only branch that didn’t call its female members by an acronym. While options such as Dainty Devil Dogs, Glamourines, WAMs, Women’s Leatherneck Aids and Sub-Marines were tossed around, Holcomb wouldn’t use any of those. Women who entered the Marines were just that.

And the reserve’s biggest contribution, according to Martin, was that it helped dispel myths that women didn’t have a place in the military beyond being nurses. Even more impressive, she said, they did so during wartime.

“They were trailblazers,” Martin said. “They were setting the stage for women to become permanent members of the military.”

Still, those interested in serving initially could not be married to a Marine (Arthur later married a fellow Marine) and weren’t allowed to have children under 18 years old, Martin said. Other qualifications included being at least 60 inches tall, weighing a minimum of 95 pounds and ranging in age from 20 to 35.

“As you see in Bea’s profile, I think 21 was the minimum age you had to have parental consent, which is interesting because men going into the military at 18 could enlist without parental consent,” Martin said.

Called to active duty

In a letter dated March 18, 1943, Arthur was called to active duty and instructed to report to the U.S. Naval Training School, Hunter College, in the Bronx, eight days later.

Russell Davis, of the Maryland Unemployment Compensation Board, penned a letter of recommendation for Arthur, having known the Frankel family for several years.

“She has always been looked upon as a leader by all her associates in the school and in the community,” Davis wrote, “and in my opinion, possesses every qualification for leadership in the organization to which she is now making application.”

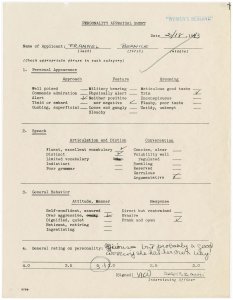

Arthur also underwent two personality appraisals. The first, conducted by Ensign V.K. Outwin, cited Arthur’s appearance as alert, trim and neither positive nor negative; her speech as fluent and distinct, while argumentative; and her general behavior as over aggressive, frank and open.

The second appraisal – from an officer whose signature is illegible – reported Arthur’s appearance was well-poised with military bearing posture and meticulous good taste; her vocabulary limited and conversation reserved; and her general behavior as ingratiating, frank and open.

Men’s service records, according to Martin, did not include “equivalent personality profiles,” possibly because the Marine Corps was still trying to figure out the inclusion of women.

While sexism could have played a role in the appraisals, according to Martin, the focus on personal appearance does make sense.

“There was such a concern about women losing their femininity going into the military,” Martin said. ”… Each branch put a lot of effort into playing up the femininity of their enlistees.”

Rising through the ranks for Bea Arthur

Arthur was promoted to private first class on May 1, 1943, while assigned to Headquarters Battalion, Company E.

Having enlisted in the Marine Corps to be a truck driver, according to her service records, she requested a transfer in June 1943 to Motor Transport School in North Carolina, believing she would be “of more value to the Marine Corps in this duty because of past experience.”

She reported to Camp Lejeune the following month and was one of two women promoted to corporal from the Specialist Schools Detachment, Marine Corps Women’s Reserve Schools. In December 1943, she joined 11 others in another promotion, this time to sergeant.

While women taking on roles as dispatchers and truck drivers, as Arthur had done, were common, Martin said it was unique that Arthur requested those roles.

“Especially considering young women from New York City had probably never driven before,” Martin said.

Plus, Browne said those specialties go “against the narrative of women in the service.”

While a member of the Aviation Women’s Reserve Squadron 17, out of Cherry Point, North Carolina, Arthur married fellow Marine Robert Aurthur and requested a name change to Bernice Aurthur.

RELATED: Marine Corps Reserve opened ‘a million doors’ for Walmart executive

In January 1945, Arthur was again promoted, this time to the rank of staff sergeant. She was honorably discharged Sept. 26, 1945.

Becoming a staff sergeant, Martin said, shows Arthur’s skill, talent and leadership.

“The fact that she was able to attain that, she must have been very good at what she did,” Martin said.

Bea Arthur service denial a ‘generational perspective?’

Despite her talents, Arthur’s denial of her Marine Corps career, according to Browne, makes sense from a “generational perspective” and how women in the military have been viewed in the past.

“I don’t hear a lot of women of the silent generation or contemporaries of Bea Arthur that would say, ‘Yes, I’m a veteran. I served.’ That’s reserved for men,” Browne said.

Martin, however, viewed Arthur’s statement more as a dismissal than a denial. Still, she said it’s “not uncommon for people to downplay their service.” In Arthur’s role as a public figure, Martin said that might have been the case.

“I do find it odd for someone to completely deny,” Martin said, “but I don’t know that that kind of goes to her as a person, she felt it was taking away from people who had seen combat. It’s hard to know.”

To Browne, it’s more interesting that Arthur didn’t talk about her service, given the length of her enlistment.

“I think it’s interesting she’s having all these experiences, and once she went to acting school, that’s what she stuck with…,” Browne said. “[I wonder] if she maybe intended to stay in service and couldn’t or didn’t for some reason. It seemed like this was a turning point in her life and work where she was ready to commit to something more long term.”

That long-term commitment led to several sitcom guest spots, her role as Maude on “All in the Family” in the early 1970s that turned into a spin-off lasting 141 episodes before landing “The Golden Girls.” She received a combined 15 Emmy nominations and awards, including Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series for her work on “Maude” and “The Golden Girls.”

It’s also possible, according to Browne, that because of her involvement in liberal and progressive causes, that Arthur didn’t want to be associated with military service.

When contacted via email, Arthur’s son Daniel Saks declined to be interviewed, but wrote that she “almost never” spoke about her time in the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, “beyond saying she could drive any vehicle.”

And though Arthur’s service and denials both are matters of public record, Browne can’t help but wonder, “How interesting would it be if she were proud of that service?”

To view Arthur’s complete service record, visit the National Archives website.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated which president signed Public Law 689. It has since been corrected.

Read comments