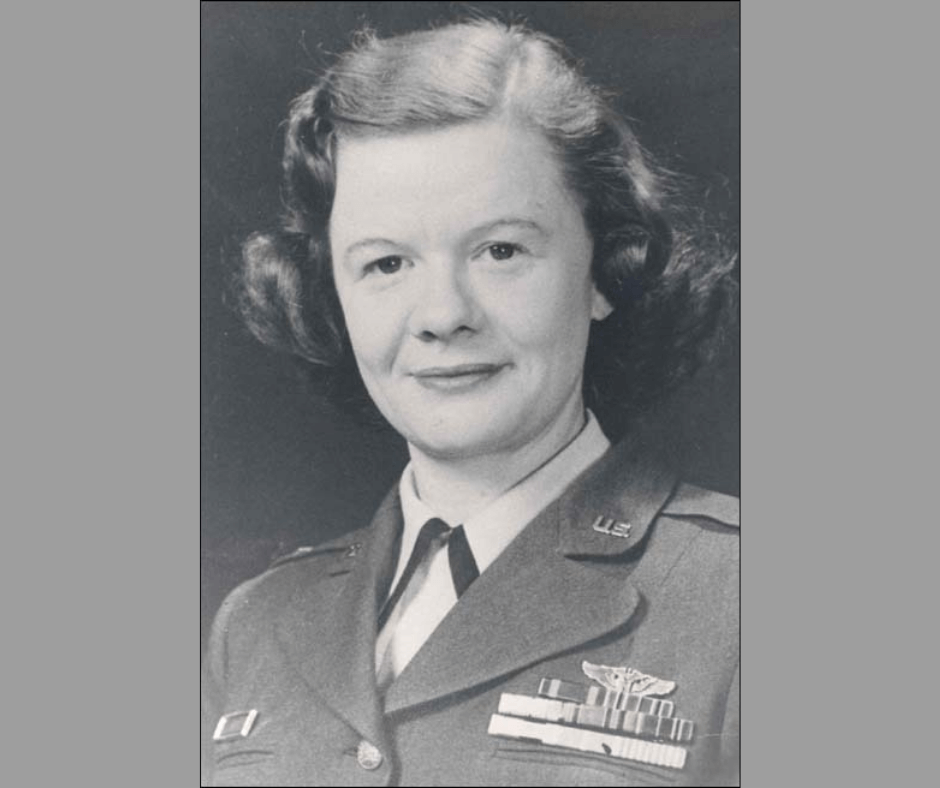

Though retired Col. Norma Parsons pursued everything in high school that was pursuable, she maintained that she “didn’t do anything outstanding.” But by 1956, when she became the first woman to join the National Guard, it was soon realized that she was the only woman in many spaces, earning her many accolades.

In a 1991 interview with Air Force 1st Lt. Melinda Hess for an Air Force Medical Service oral history project, Parsons, who was born and raised in Maine, said that seeing nurses leave a hospital near her home in their white uniforms was the biggest influence on her choosing that profession. However, she stated that there weren’t a lot of opportunities in the 1930s for women.

After graduating from nursing school in 1936, she worked at a hospital in New York, New York. Then in 1941, she joined the Army Air Corps, trained to be a flight nurse and shipped off to Naples, Italy. Parsons told Hess that they couldn’t get into the harbor at first, since the city was under attack.

In addition to Italy, Parsons helped evacuate and treat wounded soldiers in France, North Africa, India, Japan, and what was then known as China Burma (now Myanmar) India Theater. While in India, she and other nurses received permission to wear slacks to protect against malaria.

Making progress for flight nurses

It wasn’t until December 1942 that flight nurses were awarded relative rank, thanks to Public Law 828. It gave them the pay and allowances equal to a commissioned officer with no dependents and opened the opportunity to reach colonel.

Parsons made it easier for nurses to stay on the go by condensing the bare necessities of the supplies in their foot lockers — usually carried by male medical technicians, who weren’t always available — down to smaller kits.

“I went down to maintenance, a couple of us, and we had them make a medical kit. And do you know, the ones they have today are very similar to that?” Parsons told Hess.

After the war, Parsons left the active duty Army Air Corps. For a while she took care of an ill grandmother back home in Maine, and after the grandmother’s death, Parsons resumed her nursing career in New York.

When the Korean War started in 1950, she returned to service, joining the Air Force, which split from the Army in 1947, and was promoted to captain. Parsons told Hess that nurses knew more about their patients, thanks to doctors’ writing more legibly.

RELATED: Ms. Veteran America 2021 sheds light on inequalities in resources for women veterans

Parsons and her team once again got innovative – instead of having to look for and clean a thermometer for each patient, they attached one to each litter using a plastic straw, scotch tape and leather straps.

A precursor to becoming the first woman to join the National Guard, Parsons flew closer to the front lines to evacuate injured men than any other woman while serving in Korea; was the only American nurse to escort the first men returned from North Korea in a 1952 prisoner exchange; and became one of the few women to be awarded the Air Medal.

Norma Parsons enters National Guard

Big changes were ahead for the reserve components. Provisions of the Armed Forces Reserve Act of 1952 allowed women to join the Army and Air Force reserves; in 1955, the National Guard Bureau started letting female augmentees work in hospital units.

But if a Guard unit was mobilized, the nurses would go back to their reserve unit, according to Michael Dale Doubler’s “The National Guard and Reserve: A Reference Handbook.” Public Law 845, enacted in July 1956, authorized female officers to join the National Guard.

Parsons had returned to reserve status after Korea, and resumed her civilian nursing career. She was attached to the New York National Guard’s 106th Tactical Hospital until Sept. 14, 1956, when she left the reserve and officially became the first woman in the National Guard.

Over the next 12 years, Parsons kept innovating. As the only nurse formally in the 106th, she took the title chief nurse, was promoted to major, and went on recruiting trips to nurse training schools. When there was lag time between when nurses joined the unit and when they could go to flight school, she created a training program.

By the mid-1980s, when Jenny Williamson-Duca joined the Delaware Air National Guard, quite a bit had changed. Women were allowed to enlist without prior service starting after the Vietnam War. She served as a medical technician, so she was one of the people carrying boxes of supplies, but in a flight suit instead of a dress.

“It seemed like everyone was the same,” said Williamson-Duca, who served from 1984 to 1991, making technical sergeant before getting out after the Gulf War. “I’d love to know how things are now,” she said.