by Jennifer G. Williams

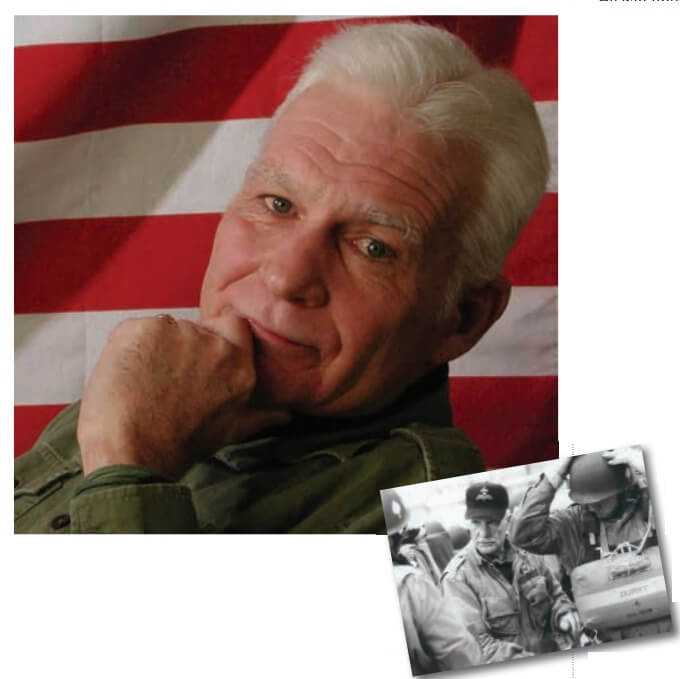

Talking with Retired Marine Captain Dale Dye about his work in Hollywood, both in front of and behind the camera.

Dale Dye came to Hollywood in the mid-1980s on a mission. The recently retired Marine captain who earned three Purple Hearts in Vietnam wanted to correct a wrong he felt went back decades.

“I’d been a movie buff all my life — a fan in particular of war movies, but I found that the vast majority of them pissed me off. I would see stuff and say, that’s nonsense! Crapola!” he says. “I didn’t know a lot about the motion picture business, but I thought what the hell — I’ll come out to LA and tell these guys that they’re wrong, I know why they’re wrong and I know how to fix it.”

It was a tough sell.

“I was having a hard time getting anyone to listen to me,” he says. “There had been technical advisors for years, but what I discovered is that it really was superficial — they explained which sides the ribbons went on, and told them what rifle to use, and that was all Hollywood wanted to hear. I thought that was the chink in the armor.”

Those who serve in the military have a special way of looking at life and dealing with each other, explains Dye. It was difficult for the actors in these movies to understand, and even more difficult for them to get right on film.

“What was needed was someone who could give them a taste of that, someone who could give them a little touchstone that would improve their performances,” he says. “But no one wanted to listen.”

Big Time

That is until Dye heard about a then, little-known director who was about to do a Vietnam War film based on his own experiences as a combat infantryman in Vietnam. “I thought — this guy will get it,” says Dye. “He will understand why we need to train the actors in a very special, immersive way, so they understand who we were at 18, 19 and 20 in Vietnam. And they can then portray that onscreen.” So Dye jumped through some hoops to get in touch with Oliver Stone (“Because he was a director and I was this nobody,” he explains), and got his chance. “In a quick, two-minute drill, I told him what I thought was wrong and how I thought we should fix it — i.e. train the actors as we were trained. Let them live the experience so they can bring it to the screen.“

Stone got it, and allowed Dye to take 33 actors into the mountain jungles of the Philippines for three weeks before they started shooting. At the time, most were relative unknowns — Charlie Sheen, Forest Whitaker, Tom Berenger, Willem Dafoe, Johnny Depp. “He let me teach them,” says Dye. “And when I brought them down out of the hills, [Stone] took one look at them and said, ‘yeah, they get it; they can do this film.’”

“And we completed a little $5 million project called Platoon,” says Dye. “We brought it home and we promptly blew everything off of the stage. We won four academy awards including Best Picture. Oliver was kind enough to acknowledge that my efforts were significant in making that film. And from that time on, we got hot and we got big.”

All of a sudden, he says, “The phones were ringing and everybody wanted a piece of my way. Since then, we’ve done huge projects. And we’ve always done them the same way — we’ve insisted on training the actors, and it has become kinda the way to go in Hollywood these days.”

And while Dye worked with Stone on several other movies, including Born on the Fourth of July, he also began working with other Hollywood heavyweights, including Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg, with whom he collaborated on several projects, including Saving Private Ryan and Band of Brothers.

“That’s tall cotton — I’ve been very fortunate,” Dye says. “I like to think the work I’ve done speaks for itself … nothing succeeds like success in Hollywood.”

Movie work can be unpredictable, with three projects one year and then three years with nothing, so Dye and his company have expanded to include other projects, including as an advisor for the Medal of Honor video game series, music videos with Alice in Chains and Green Day, and various advertising campaigns. Dye even started a publishing company, Warrior Publishing Group. He has authored several books, including the popular Shake Davis series, and shows no sign of stopping.

Collaborative Effort

Dye says that “getting it right” often means making compromises on set. Sometimes, a director doesn’t want to hear what’s right, and just wants a scene go a certain way. When that happens, he says, “you have to be smart about it. You have to understand that you’re not making documentaries — there has to be some license for drama for entertainment, for momentum and pacing in the film. You do what you typically would do as a military man in battle and you pick your fights.”

Dye has noticed that more and more people in movies and television look to military advisors, but he warns that it’s a difficult row to hoe. “Just because you did four years in the Army and you had three deployments to the sand box, it doesn’t mean you can be a successful military advisor,” he says. “You’ve got to be part teacher, psychologist, part artist, you need to be a dramatist. Those are difficult things. It’s not just about teaching them to fire a rifle. There’s much, much, much more to it.”

Dye says he’s seen “hundreds” of movies on which he wishes he had been called to help. “The Boys of Company C, Heartbreak Ridge, you know — those are just two off the top of my head. They just needed help on those,” he says.

One of the thin lines Dye constantly has to maneuver is helping nonmilitary viewers understand what is going on while staying true to military and veteran audiences. “You have to realize, if you want to get your message across, if you want to shine that long-overdue light on the sacrifice of the men and women who wear our uniform, then you have to go to the medium that scores, and in this generation, it’s motion pictures, television, the internet,” he says.

“We live in an age of almost instantaneous communication and media saturation,” he says. “We’re constantly connected with images and our news comes to us almost instantaneously from battlefields around the world, so people who have no military experience very often know what it should look like, because whether they like it or not, they’ve been inundated by these images online, on television and through magazines and so on. So I think it’s always a mistake to underestimate your civilian audience.”

And while Dye says he will always have a soft spot for Platoon, he really enjoys working on miniseries. He’s done a few, including Band of Brothers and The Pacific, each of which took about a year of his life to make. Dye not only served as a technical advisor, but also portrayed Col. Robert Sink, the famed commander of the 506th Infantry Regiment, in HBO’s Band of Brothers.

“In a normal motion picture, you have about 120 minutes to build the characters, tell the story and wrap it up. That causes you to have to hurry up through a lot of things,” he says. “But with a miniseries, with 10 or 12 episodes, you have time to explore the characters, you have time to let the actor build the character, and you’ve got time to explore relationships in a unit and how the unit changes over time.”

Kudos

Recently named as a 2017 Honorary Member of the 506th Infantry Regiment, Dye says recognition by fellow service members and veterans means more to him than any Hollywood award.

“When I go to Camp Pendleton or to Fort Bragg or any of the other places and the guys come up and pat me on the back and say, ‘there you go, skipper, that was the one.’ To me, that’s really the Academy Award, that’s my Oscar.”

Those recognitions mean so much, says Dye. “You know, the press will never pay much attention to that and that’s fine,” he says, “but those kind of little kudos say to me that I was right to begin with and I’m still doing it right.”