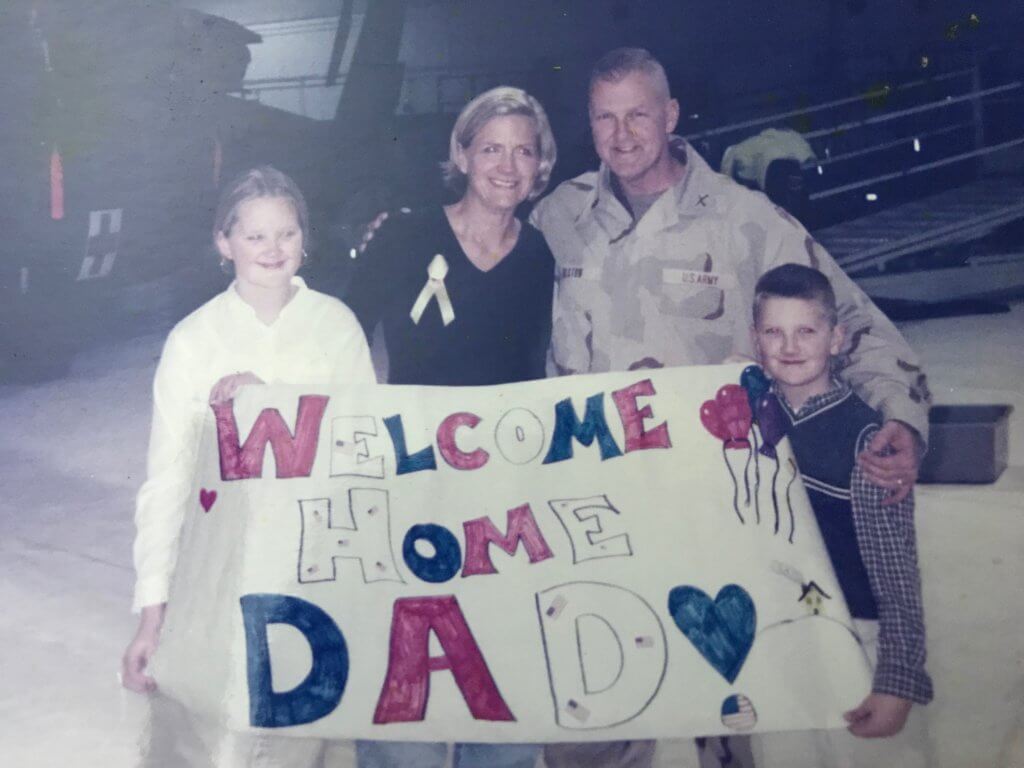

National Guard spouse June Heston frantically searched for answers about why her husband, Brig. Gen. Michael Heston was fading away in front of her eyes.

The Vermont Army National Guard Assistant Adjutant General was sick for 10 months and lost 75 pounds before doctors realized what was wrong. Medical providers neglected to connect the symptoms he was facing with his three deployments to Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom from 2003 to 2012.

“We saw so many different doctors. One doctor, in particular, said, ‘We don’t know what it is, but it’s not cancer.’ He said that more than once, but I kind of knew it was bad,” said June Heston, later realizing that her husband’s comments about a black cloud while he was deployed held the key to his diagnosis.

“He said there was black soot everywhere,” Heston said. “They moved one burn pit because it was affecting the engines on the jets, so they moved the burn pit, and it was closer to where people were living.”

Burn pit statistics

According to nonprofit BurnPits360, up to 227 metric tons of hazardous waste was burned at operating bases with jet fuel in large pits in the ground. Batteries, medical waste, plastics and other dangerous materials were disposed of in the burn pits, creating a toxic cloud now linked to neurological disorders, pulmonary diseases and rare forms of cancer in those who worked near the area.

The Senate Veterans Affairs Committee is currently working on a bipartisan deal to expand health care resources and benefits for 3.5 million service members exposed to burn pits.

But the federal aid will come too late for Heston, whose husband died in 2018 after a pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

“When he was diagnosed, he said, ‘This isn’t going to take me,’ and he fought,'” said Heston, recalling he continued to work for the Vermont National Guard almost every day.

He retired just three months before he died.

‘You can be honest and vulnerable’

When June shared the story of his fight away from the battlefield with the media, she was contacted by a member of the Tragedy Assistance Program For Survivors (TAPS), a nonprofit that provides compassionate care to those grieving the death of a military loved one.

She found healing and comfort from programs that connected her with other surviving family members experiencing the same emotions.

“When others witness grief, it’s so uncomfortable for most people,” Heston said. “But you can be honest and vulnerable around your TAPS family and not just the staff, but the people that you meet.”

TAPS also ensured that Heston’s life was honored at a New England Patriot’s game the year following his death through the organization’s partnership with the NFL Salute to Service Program. Michael was an avid Patriots fan.

Guard tragedy prompts creation of TAPS

The camaraderie and comfort provided by the program initially came from a different National Guard tragedy.

TAPS Founder and President Bonnie Carroll’s husband, Brig. Gen. Thomas C. Carroll, was killed with seven others in 1992 when a C-12F twin-engine Beechcraft crashed near Juneau, Alaska.

At the time, Bonnie was trained to deal with trauma through her role in the Critical Incident Stress Debriefing Team with the Alaska National Guard. However, she learned all of the training possible could never prepare her for the sudden loss of her husband.

“It is a very different experience when it is personal,” Bonnie said. “Your whole world has just completely been shattered.”

She found comfort in spending time with the other surviving family members of the crash and started a small program locally. It eventually expanded into the international program it is today. TAPS now connects with 25 new survivors each day and also provides 24/7 free peer support and connection to survivor resources. They also host retreats and seminars and provide free assistance to obtain applicable survivor benefits.

“You know, nobody can fix what has happened. Nobody could bring my husband back. But what they could do is just be with me in that space,” Bonnie said.

TAPS goals

However, Carroll said the program doesn’t reach as many Guard and reserve members as desired. In 2021, 9% of new people helped by the nonprofit were families of those who served in the Guard or reserves, compared to 43% of loved ones with active-duty counterparts. She hopes government partnerships will expand the program’s reach.

TAPS also is lobbying for aid for all military members who die due to illness and started a Caregiver to Survivor program. An Illness Loss Survivor Survey of nearly 1,000 survivors, conducted in 2021, found that misdiagnosis occurred before the death of about 40% of post-9/11 service members. The organization hopes connecting military families dealing with illness will help improve medical outcomes.

“We are embraced by so many who have traveled this path before us,” Heston said, adding that she’s connected with many who have experienced the same circumstances as her husband. “We feel like we weren’t alone.”

As Memorial Day approaches, Heston asked people to honor soldiers who didn’t directly die in combat but lost a different battle after they returned home. She considers her husband a hero for his dedication to serving the country.

“I believe that if he were asked to do it again, he would do it if he had the chance,” she said.