The last time that the United States faced a national health crisis as deadly as the COVID-19 pandemic, antibiotics did not exist.

Neither did the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. When the first case of the Spanish flu arrived in the United States at an Army camp in Fort Riley, Kansas, in the spring of 1918, World War I dominated the headlines.

That pandemic resulted in roughly 50 million deaths worldwide in 1918-19, and about 500 million people were infected. Approximately 675,000 Americans died.

“The flu was a disaster,’’ said Carol Byerly, author of “Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army during World War I.’’ “It killed more people in the military than the war did, and so they tried to understand it. They didn’t understand viruses at the time.’’

More than 1,400 National Guard Medical Services personnel were sent overseas, leaving only 222 NGMS officers at home to assist with controlling the spread of influenza and pneumonia, according to the National Guard Bureau. (By comparison, a high of 47,000 National Guard members supported the COVID-19 response in May.) In 1918, most of the National Guard’s members — more than 12,000 officers and nearly 367,000 soldiers — served in World War I.

“[In] 1918, the pandemic hit, and most of the medical services were deployed overseas,’’ said Dr. Richard Clark, historian of the National Guard Bureau. “The National Guard mobilized its medical forces to augment stateside military forces to help with the military bases.’’

Read: Guard leaders talk pandemic, readiness, career progression

The National Guard previously had not assisted with such a widespread health emergency. For more than three months, beginning in September 1858, the New York National Guard helped alleviate a disturbance during a yellow-fever quarantine on Staten Island. In late 1910 and early 1911, the Michigan National Guard enforced a quarantine of smallpox patients at a state asylum. Those missions did not provide medical support, though.

“The thought of using [the National Guard] in a medical capacity to respond domestically had not really been thought about until that point,’’ Clark said.

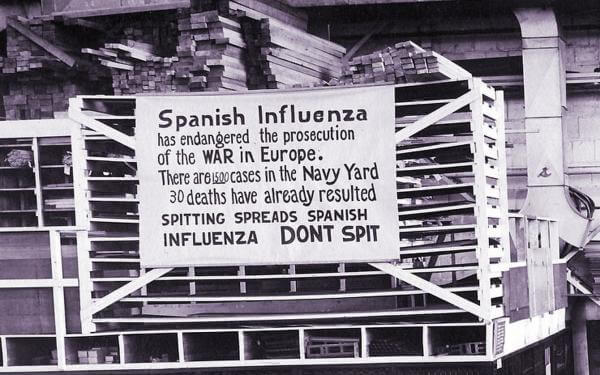

The military’s role in spreading the Spanish flu is undeniable. As soldiers moved between camps in the U.S. or were deployed to France, the number of infections increased. Some Army camps, such as Camp Devens near Boston, were particularly hard-hit. When ships carrying troops returned from overseas, more soldiers got sick.

War-bond parades left citizens susceptible to infection, too, including one in Philadelphia, attended by 200,000 people, that resulted in a spike of cases. Despite the rising totals, the pandemic was downplayed.

“Every day, you read the newspaper, and a couple of cases were developed in the city, and officers were saying, ‘It’s no big deal,’’’ Dr. Alex Navarro, the assistant director for the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan. “[Then] there would be hundreds and hundreds of cases, and this is something very serious. Very rapidly, they had to deal with the threat.

“The one major issue was that there was a shortage of doctors and nurses, as well as some medical supplies like surgical gauze and masks, so the war effort definitely hindered that medical response.’’

Some preventive measures, including social distancing and mask laws, were put into place. The military tried quarantining camps and limiting troop mobilizations, but those restrictions were not sustainable during wartime, Navarro said. They even stopped the draft in October, a month before World War I ended, Byerly said.

“They didn’t want to stop the draft,’’ Byerly said. “They didn’t want to reduce crowding on the ships and in the training camps. They didn’t want to send more nurses and doctors to the soldiers, but that is what you have to do in order to take care of your personnel.’’

A total of 43,000 U.S. service members died because of the pandemic. More than a quarter of the Army’s soldiers, about 1 million men, became infected, and at least 106,000 Navy sailors were hospitalized, according to Byerly. The National Guard has no records of how many of its members died or were infected.

While the National Guard’s role in combating the Spanish flu a century ago was minimal, a valuable lesson came out of that pandemic, Clark said. Officials began preparing to offer more support during national health emergencies. The wisdom of that decision is being felt a century later.

“We’re not going through something new,’’ Clark said.

“History doesn’t necessarily repeat itself, but it rhymes, so the lessons of the past should not be taken as a one-for-one example or a guide to what we need to do today. Many of the details, much of the context is very, very different, but what you can use the past as a guide for is for critical thinking about the situation. … What is the same, and what is different?’’